Pain Management in the Recovery Room: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ __NOEDITSECTION__ | __NOTOC__ __NOEDITSECTION__ | ||

REFERENCE: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32129952/ | REFERENCE: [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32129952/ Pain assessment and management in children in the postoperative period: A review of the most commonly used postoperative pain assessment tools, new diagnostic methods and the latest guidelines for postoperative pain therapy in children] | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Assessing the patient’s pain level is probably the main issue, as it can be challenging or excessively subjective. In contrast to what happens among adults, there is a lack of direct and objective indicators of childrens’ pain severity. Aspects such as behavior, cognitive development and ethnicity add complexity to this evaluation. There can hardly be a satisfactory assessment without an interdisciplinary approach. | Assessing the patient’s pain level is probably the main issue, as it can be challenging or excessively subjective. In contrast to what happens among adults, there is a lack of direct and objective indicators of childrens’ pain severity. Aspects such as behavior, cognitive development and ethnicity add complexity to this evaluation. There can hardly be a satisfactory assessment without an interdisciplinary approach. | ||

[[File:Table 2.png|thumb]] | |||

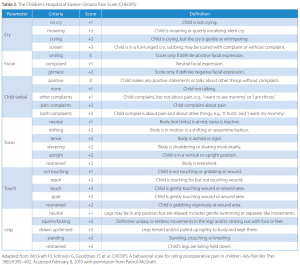

In terms of propedeutic signs, clinical observation must include facial expressions, limbs’ motion, posture, agitation level, verbal content and whether or not the infant touches or points the wound. There’s been an effort to systematize these signs through pain scores, such as CHEOPS, FLACC, CHIPPS, FPS, VAP, OPS and MOPS, which can be useful tools. More recent attempts to enclose objectivity to this assessment are notable, including the skin conductance algesimeter and algorithms that evaluate the heart rate variability. | In terms of propedeutic signs, clinical observation must include facial expressions, limbs’ motion, posture, agitation level, verbal content and whether or not the infant touches or points the wound. There’s been an effort to systematize these signs through pain scores, such as CHEOPS, FLACC, CHIPPS, FPS, VAP, OPS and MOPS, which can be useful tools (see table). More recent attempts to enclose objectivity to this assessment are notable, including the skin conductance algesimeter and algorithms that evaluate the heart rate variability. | ||

Once correctly diagnosed, pain management in children can more easily be addressed. Fundamentally, basic analgesics, which are widely accessible, such as NSAIDs and paracetamol should be administered, promoting an opioid use reduction. Opioid use should be limited to the operative and early postoperative set, in order to minimize risks related to its collateral effects. Patients receiving opioids must be closely monitored, specially in its respiratory and neurologic functions. Basic analgesics can be administered orally, intravenously or rectally, with low incidence of adverse effects. | |||

Latest revision as of 11:58, 31 May 2024

A correct pain management of children in the postoperative recovery room can be determinant for many health outcomes. There is plenty of evidence suggesting notable physiological dysfunction related to poor analgesia, in this scenario, and beneficial results of an effective pain management are also well documented. Postoperative pain, for instance, prolongs hospitalization and delays recovery.

Assessing the patient’s pain level is probably the main issue, as it can be challenging or excessively subjective. In contrast to what happens among adults, there is a lack of direct and objective indicators of childrens’ pain severity. Aspects such as behavior, cognitive development and ethnicity add complexity to this evaluation. There can hardly be a satisfactory assessment without an interdisciplinary approach.

In terms of propedeutic signs, clinical observation must include facial expressions, limbs’ motion, posture, agitation level, verbal content and whether or not the infant touches or points the wound. There’s been an effort to systematize these signs through pain scores, such as CHEOPS, FLACC, CHIPPS, FPS, VAP, OPS and MOPS, which can be useful tools (see table). More recent attempts to enclose objectivity to this assessment are notable, including the skin conductance algesimeter and algorithms that evaluate the heart rate variability.

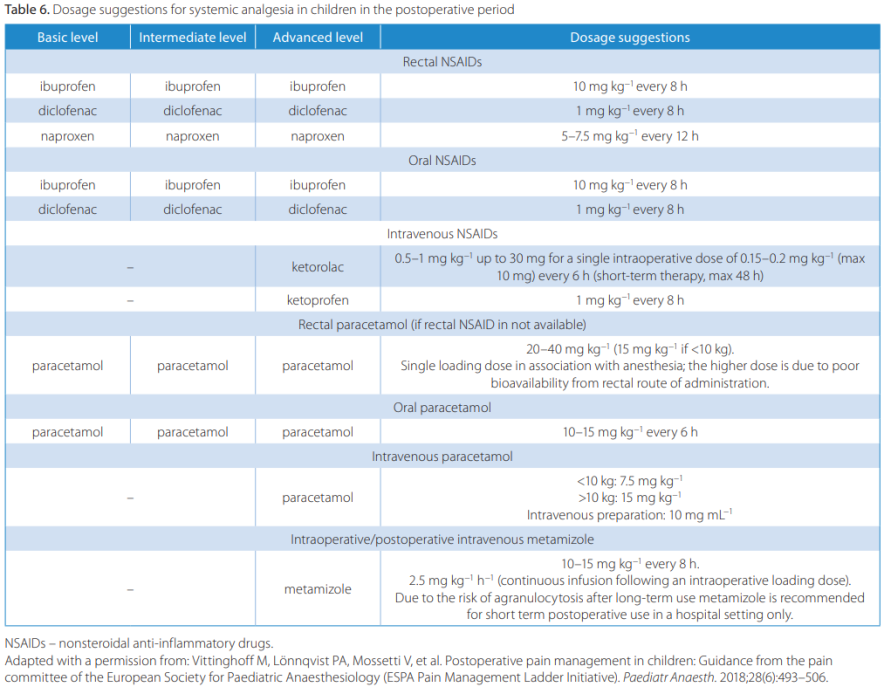

Once correctly diagnosed, pain management in children can more easily be addressed. Fundamentally, basic analgesics, which are widely accessible, such as NSAIDs and paracetamol should be administered, promoting an opioid use reduction. Opioid use should be limited to the operative and early postoperative set, in order to minimize risks related to its collateral effects. Patients receiving opioids must be closely monitored, specially in its respiratory and neurologic functions. Basic analgesics can be administered orally, intravenously or rectally, with low incidence of adverse effects.

In the following table, guidelines published by the European Society for Paediatric Anaesthesiology Pain Committee (2018).