Paediatric difficult airway management: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 277: | Line 277: | ||

techniques ‘should be considered’. | techniques ‘should be considered’. | ||

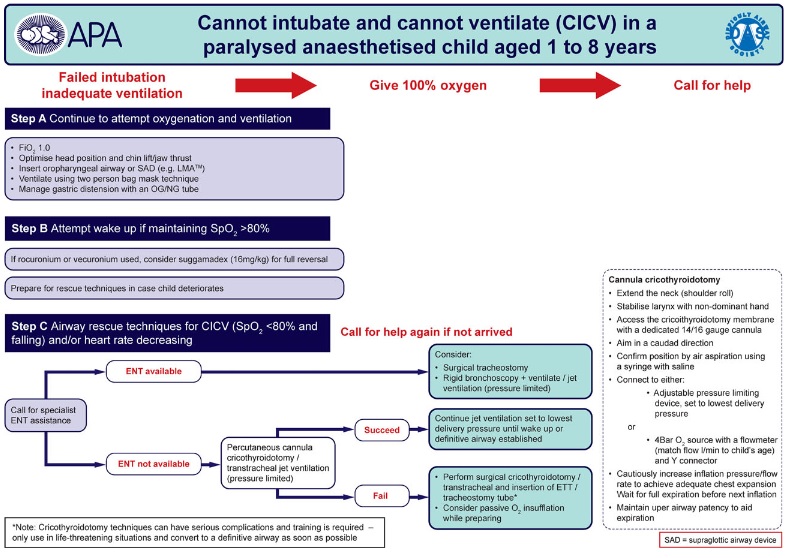

[[File:CICV_Algorithm.jpg|800px|center|thumb|Figure 3: Can’t intubate can’t ventilate algorithm. Reproduced with kind permission of Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists ]] | |||

[[File:CICV_Algorithm.jpg|800px|center|thumb|Figure 3: Can’t intubate can’t ventilate algorithm. Reproduced with kind permission of Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists ]] | |||

== REFERENCES == | == REFERENCES == | ||

Revision as of 16:23, 12 February 2023

This page is under construction, converting the originally formatted pdf from the WFSA site with wiki embellishments.

Originally from Update in Anaesthesia | www.wfsahq.org/resources/update-in-anaesthesia

Michelle C White* and Jonathan M Linton

- *Correspondence email: mcwdoc@doctors.org.uk

Dr Michelle White, Consultant Anaesthetist, Mercy Ships, Guinea

Dr Jonathan Linton, Specialist Trainee Anaesthesia, University Hospital, Southampton, UK

| Unexpected difficult airways in paediatric practice are rare. Many problems can be prevented by routine preoperative airway assessment, pre- xygenation, and preparation of equipment. A simple step-wise approach to management improves outcome. Anaesthetists have a responsibility to be familiar with airway algorithms and make pragmatic modifications to account for available resources. |

|---|

INTRODUCTION

Airway management in children is generally straightforward in experienced hands. Problems are more common for the non-paediatric anaesthetist, and are a major cause of anaesthesia-related morbidity and mortality. Genuine ‘difficult airways’ are rare in children compared to adults and many are predictable. However, differences in adult and paediatric physiology mean irreversible hypoxic damage occurs more quickly in children if there is an airway problem. Simple stepwise strategies are essential. Many guidelines exist for the management of difficult airways in adults, but there are few specifically designed for use in children. The aim of this article is to outline the basic principles of paediatric airway assessment and to discuss the management of unexpected and expected difficult paediatric airways. Evidence to support best practice is difficult to obtain for unpredictable events such as management of the paediatric difficult airway, and there is a lack of high quality data. Many new devices and techniques are available, but most are evaluated in healthy children or simulated ‘difficult’ situations. Due to this lack of evidence, guidelines are often based on a consensus of expert opinion, which may have a bias against newer devices and techniques, or indeed bias towards the latest technique that has gained popularity. This review takes a pragmatic and cautious approach in applying existing guidelines to settings where experts and a range of technology are not always available.

BACKGROUND

Management of the difficult airway can be divided into three critical areas:

- 1. Difficult mask ventilation

- 2. Difficult tracheal intubation

- 3. Can’t intubate and can’t ventilate (CICV).

The incidence of difficult airways in children is unknown. The incidence of impossible mask ventilation is reported as 0.15%, and is more frequently encountered by inexperienced paediatric anaesthetists. Difficult intubation ranges from 0.05%, rising to 0.57% in children less than one year of age.[1] Difficult intubation is more common in children with cleft lip and palate (4.7%) and cardiac abnormalities (1.25%), most likely related to associated syndromes or limited cardiac reserve.

An audit of difficult airway management in the UK in 2001 (the 4th National Audit Project, NAP 4), prospectively measured major airway complications in almost 115,000 patients undergoing anaesthesia.[2] Children comprised a small proportion of the total population, and complications were rare (only 7-8% of total complications).

Common contributing factors to bad outcomes were:

- • Poor airway assessment

- • Poor planning

- • ‘Failure to plan for failure’

- • Repeated attempts at intubations

- • Lack of monitoring (oxygen saturation and capnography)

- • Slow response to hypoxia resulting in bradycardia leading to cardiac arrest

- • Failure to use devices such as the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) when faced with a difficult intubation.

One of the key findings in NAP4 was the ‘failure to plan for failure’. Airway management plans should always include a back-up plan to use if the first plan fails. Whenever unexpected difficulties occur, seek experienced help immediately. Another key finding of NAP4 was that repeated attempts at intubation can cause severe airway oedema in children and worsen the situation, hence their recommendation, ‘a change of approach is required, not repeated use of a technique that has already failed’. Many countries have adult guidelines for management each of difficult airways, but few have child specific guidelines. The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (APA) published paediatric guidelines in 2012, which are shown in Figures 1-3 and form the basis for management of the unexpected difficult airway discussed here.[3]

AIRWAY ASSESSMENT

Proper airway assessment, proper planning for airway management, and the use of monitoring are essential basic principles for safe anaesthesia in children. Airway assessment may be considered in two parts:

Will facemask ventilation be difficult?

- • A tumour or abnormal face shape may prevent the facemask from

sealing easily over the face.

- • Syndromes associated with midface hypoplasia

- • Children with severe obstructive sleep apnoea (e.g. tonsillar

hypertrophy).

Will intubation be difficult?

Factors that may predict difficult intubation in children include:

- • Mandibular hypoplasia e.g. syndromes such as Pierre Robin

- • Poor mouth opening

- • Obstructive sleep apnoea

- • Stridor

- • Syndromes associated with facial asymmetry. Note ear

abnormalities are often associated (e.g. Goldenhar syndrome).

Various tests and scoring systems have been suggested for use in

adults. Many have a very poor sensitivity and/or specificity and are

not validated in children. However, assessment of the following is

essential. The anaesthetist may need some ingenuity to achieve these

assessments in a small uncooperative child!

- • Mouth opening

- • Range of neck movement

- • Mandibular hypoplasia - micrognathia makes intubation difficult.

Assess the airway by observing the child in side view rather than from the front.

- • Mandibular hyperplasia - ameloblastoma may cause jaw

protrusion and can make laryngoscopy and intubation difficult

- • Inspection of the oral cavity (e.g. for intraoral masses).

The Mallampati score can be used for older children who are cooperative. Even though there is no validated scoring system in infants and young children, the anaesthetist must still make a risk assessment, and decide on the anticipated difficulty of intubation. This airway assessment must be documented in the anaesthetic record.[4]

PLAN FOR AIRWAY MANAGEMENT

After airway assessment, a structured plan for airway management is required before induction of anaesthesia. The plan must consider:

- • Choice of airway e.g. facemask, supraglottic airway device or

tracheal tube

- • Mode of ventilation e.g. spontaneous ventilation or positive

pressure

- • Monitoring e.g. pulse oximeter (minimum); end tidal carbon

dioxide.

Due to a lower functional residual capacity (FRC) and higher metabolic rate, oxygen saturation falls much faster in infants and young children than adults. Preoxygenation before induction of anaesthesia establishes a reservoir of oxygen in the lungs by displacing nitrogen. This means a patient can remain oxygenated for longer than otherwise expected, which gives more time to address unexpected airway problems. Therefore preoxygenation is an important part of the airway management plan and should form part of normal anaesthetic practice wherever possible, even in children.

THE UNEXPECTED DIFFICULT AIRWAY

Problems with airway management may be due:

- 1. Difficult mask ventilation

- 2. Difficult tracheal intubation

- 3. Can’t intubate and can’t ventilate (CICV).

The first step is to administer 100% oxygen and call for help. Another

pair of hands is always useful.

The next step is to consider – is this a problem with the equipment or the patient? All equipment should be checked prior to induction of anaesthesia to minimise the chance of equipment failure.

1. Difficult mask ventilation

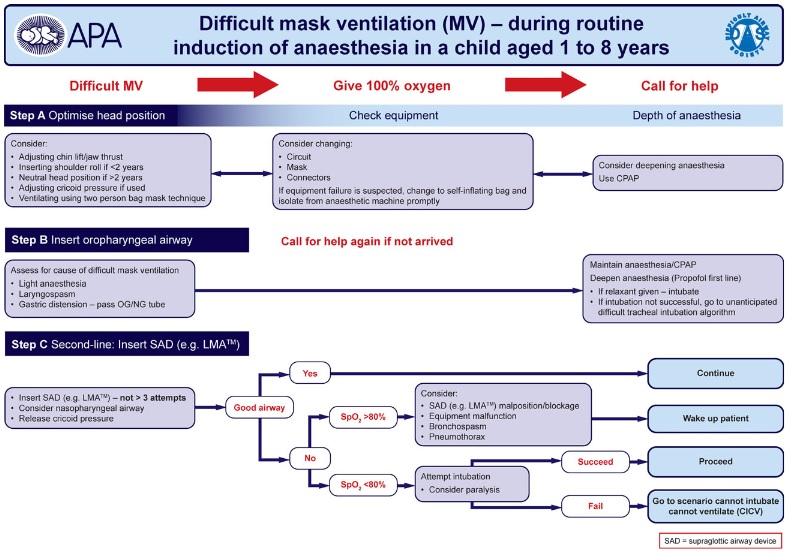

A simple algorithm for the management of difficult mask ventilation is given in Figure 1: Difficult mask ventilation algorithm. http:// www.apagbi.org.uk/sites/default/files/images/APA1-DiffMaskVent- FINAL.pdf

Difficult mask ventilation – equipment problems

Equipment failure should be excluded quickly – check the mask, circuit, and oxygen supply. Always have a self-inflating bag available in case of equipment problems.

Difficult mask ventilation – patient factors

These can be divided into anatomical or functional problems. Anatomical problems associated with difficult mask ventilation may be due to poor head positioning, large adenoids/tonsils, or due to airway obstruction from cricoid pressure (if used). Functional problems may arise in the upper or lower airways. Upper airway obstruction may be due to inadequate depth of anaesthesia and laryngospasm; lower airway problems include inflation of the stomach (very common in infants), bronchospasm or chest wall rigidity (rare).

Management of difficult mask ventilation:

- • Adjust the head position – does the child need a head roll (or

should the head roll be removed)

- • Use simple airway opening manoeuvres (chin lift, jaw thrust)

- • Apply positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP)

- • Adjust cricoid pressure if it has been used

- • Insert an oropharyngeal airway (if the patient is deep enough)

- • Increase depth of anaesthesia

- • Ventilate using a two-person technique (one holding the mask with two hands, the other ventilating by squeezing the bag)

- • Pass a nasogastric tube to deflate the stomach.

If mask ventilation is impossible despite all the above measures or the child’s oxygen saturation begins to fall:

- EITHER insert an LMA (if available),

- OR deepen anaesthesia, attempt to visualise the vocal cords and

intubate the trachea.

There is no randomised controlled trial to assess which is the best response, but insertion of an LMA is recommended first, and then intubation (Figure 1).

If oxygenation and ventilation is satisfactory through the LMA or tracheal tube then it is safe to proceed with surgery.

If in doubt, wake the child up.

2. Unexpected difficult tracheal intubation

A simple algorithm for the management of unexpected difficult tracheal intubation is given in Figure 2: Difficult tracheal intubation algorithm. http://www.apagbi.org.uk/sites/default/files/images/APA2- UnantDiffTracInt-FINAL.pdf

The key point is, if tracheal intubation fails, DO NOT simply repeat what has just failed. Multiple attempts at intubation may traumatise the airway and will cause airway oedema, which may make the child impossible to intubate. Intubation attempts must be limited to a maximum of three or four (Figure 2).

If the first intubation attempt fails, it is essential to make changes that improve the chance of successful intubation. These may include:

- • Change of personnel (a more senior anaesthetist);

- • Change of position

- • Change of equipment.

Visualisation of the larynx and successful tracheal intubation are improved by:

- • Proper positioning of the child,

- • External laryngeal manipulation

- • Adequate depth of anaesthesia and adequate muscle paralysis (if

this has been used).

Simple aids such as a bougie or stylet may make intubation straightforward even when the view of the larynx is poor. An alternate laryngoscope may also be used if available and if the operator is familiar with its use.

Straight bladed laryngoscopes are traditionally used in children under one year old, but may be useful in older children, or in patients with relative macroglossia. They can be used with a paraglossal or retromolar technique. McCoy levering laryngoscopes are also available for paediatric use, based on a Seward blade (sizes 1 and 2) and may improve the view of the larynx, particularly if the view is obstructed by a large epiglottis.

In addition to straight bladed and McCoy laryngoscopes, new alternate laryngoscopes have been developed recently (see table 1). High quality evidence supporting efficacy is largely absent in the life-threatening scenario of unexpected failed intubation. Firm recommendations cannot be made so many algorithms suggest alternate laryngoscopes/ techniques ‘should be considered’.

REFERENCES

- ↑ Weiss M, Engelhardt T. Proposal for the management of the unexpected difficult pediatric airway. Pediatr Anesth 2010; 20: 454-64. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/ doi/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03284.x/pdf

- ↑ The 4th National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society: Major Complications of Airway Management in the United Kingdom. March 2011. http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/nap4/

- ↑ The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists (APA) Guidelines for difficult airway management in children. 2012. http://www.apagbi.org.uk/publications/apaguidelines

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Guidelines for Safe Surgery 2009. http://whqlibdoc. who.int/publications/2009/9789241598552_eng.pdf and http://www.who.int/ patientsafety/safesurgery/en/